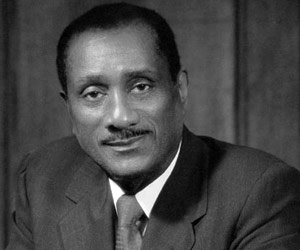

Remembering African American media pioneer John H. Johnson

By Kossi Gbêdiga

The celebration of black history during the month of February involves, among other things, honoring the legacies of influential black men and women, the likes of Marcus Garvey, W.E. Dubois, Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King, Jr., and hundreds others who have contributed to the advancement of black people. One man who clearly belongs to this pantheon, and who hasn’t got much recognition during Black History Month is the late John H. Johnson, founder of the first ever black magazine published in the United States.

When in 1942, at age 24, John Harold Johnson launched Negro Digest which, the following year, became Ebony, there were no publications in the United States committed to covering the black community. In 1942, Martin Luther King, Jr. was only 13 years old; Doug Wilder, the first black governor of modern times in the United States, was 11, and the Rev. Jesse Jackson was only one-year old. In those days, no major city in America had a black mayor. In the issue commemorating Ebony‘s 50th anniversary, John H. Johnson wrote:

“In 1942, Black men and women were struggling all over America to be called ‘Mr.’ and ‘Mrs.’ In that year we couldn’t try on hats in department stores in Baltimore, and we couldn’t try on shoes and dresses in Atlanta. We couldn’t live in hotels in downtown Chicago then, and the only public place a Black could get a meal in the downtown section of the nation’s capital was the railroad station.”

Today, basketball superstar LeBron James, baseball sensation Ryan Howard and scores of other black athletes dominate the world of sports, but, recalled John H. Johnson, in 1942 “experts said with a straight face that something in our genes made it impossible for us to play major-league baseball and basketball.” Johnson challenged that world in a significant way by redefining the image of black men and women in the United States. He wrote:

“In a world of negative Black image, we wanted to provide positive Black images. In a world that said Blacks could do few things, we wanted to say they could do anything.”

Besides his mother, Gertrude Jenkins, a woman with deep religious convictions who believed in her son, virtually everyone, including influential blacks and his own wife, Eunice Johnson, discouraged Johnson from venturing in publishing. Eunice Johnson, however, later got fully involved, being the one who chose the name Ebony, and became the director of Ebony’s Fashion Fair, an addition to the business that proved very successful.

The publishing business has never been easy, and it proved especially hard for a black pioneer in the early forties. Mindful that nobody would risk a penny on his publishing dream, Johnson used the furniture he had bought for his mother to secure a $500 loan, in addition to some creative business tricks, to publish the first issue of Negro Digest. As could be expected, a $500 initial capital, even in those days, was a drop in the bucket. Johnson’s early success–with the initial 25,000 copies of the first issue of Ebony sold out and a reprint needed–was short-lived and he had to fight one obstacle after another to keep the dream alive. He recounted his financial woes in his book, Succeeding Against the Odds, saying how he had to hide from creditors, and how, typically, he was deserted by some people who lost faith in him during the worst of times. A believer in positive thinking, Johnson did not hesitate to fire employees who doubted he would survive the challenges.

It may seem as though Johnson simply filled a void of black publications, and that his success was a sure thing, the early hardships nothwithstanding. A close look at history paints a different picture. As Ken Smikle, president of Target Market News, pointed out in a post soon after Johnson’s demise, Freedom’s Journal, the first black newspaper started in America in 1827 by two black pioneers, Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm, lasted only two years, despite its editors being hailed for their daring. Johnson’s Ebony lasted 63 years until his death in 2005 – and is still a viable business today in the able hands of his daughter Linda Johnson Rice.

Ebony is now the most visible legacy of the Johnson Publishing company, but the company has been credited with twelve titles in all, including EM (Ebony Man), Ebony Jr. and Jet, not to mention a short-lived African edition of Ebony published in South Africa. Johnson had other business interests as well. Besides developing a successful line of cosmetics, Johnson bought three radio stations, started a book company and a television production company, and had a stake in other companies. He also served on the board of directors of several major companies.

John Harold Johnson was born on January 19, 1918 in Arkansas City, Arkansas. After his father, Leroy, died in a mill accident, his mother married another mill worker. Mother and son, after visiting the World’s Fair in Chicago, decided to make it their new home and moved there in 1933. Johnson’s stepfather joined them later, but the family lived on welfare until Johnson’s stepfather found a job. Johnson, a boy from the rural south, now attended a major city high school, DuSable high school, where he recounts in his memoir that he was often taunted by the middle-class black kids who made fun of his ragged clothes and country ways.

After graduating from high school in 1936, Johnson was hired by Harry Pace, president of the Supreme Liberty Life Insurance Company, a black man who had been impressed with Johnson’s brilliant presentation at a dinner held by the Urban League. Starting as an office boy, Johnson two years later became Pace’s assistant. He was responsible, among other things, for preparing a monthly digest of newspapers articles for Pace. Thus later crystallized in his mind the idea of starting Negro Digest, a pocket-size publication patterned after Reader’s Digest which grew into an up-scale magazine titled Ebony with flashier design patterned after leading magazines such as Life.

Ken Smikle, president of Target Market News, adequately captured Johnson’s legacy in these words:

“Johnson’s passing in August at the age of 87 was not the end of his legacy. Indeed, it seems that only now is Black America taking the full measure of the impact this remarkable entrepreneur had on history, business, the civil rights movement and the nation. Only by examining his accomplishments, and hearing the testimonies of those he influenced, is a true appreciation of his work beginning to emerge. What made Johnson’s success unique is the fact that his efforts changed the world.”

Undeniably, the driving force behind John Johnson’s success was larger than his skills as a businessman who was able to survive all the obstacles on his way. He was propelled by his deep belief in himself. The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. once said: “You ought to believe something in life, believe that thing so fervently that you stand up with it till the end of your days.” So deep was Johnson’s belief in his dream, so sharp was his tenacity that he achieved enormous success, proving wrong all those who doubted him, to become in 1982 the first African American on Forbes magazine’s list of the 400 wealthiest Americans, the year Ebony‘s circulation reached 2,300,000.

But this humble pioneer didn’t take full credit for his success, stating, in the special issue marking Ebony‘s 50th anniversary, that God simply used him to reach that end. Looking back at his struggle to succeed, he called it a time of darkness, adding, however, that “darkness was light enough.”