2015, a milestone in democratic advancement in Africa

BY JIBRIL TURE AND MODUPE ABIOLA

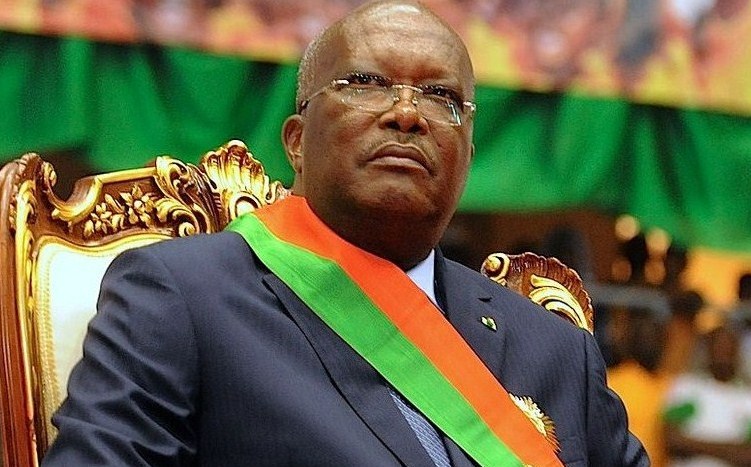

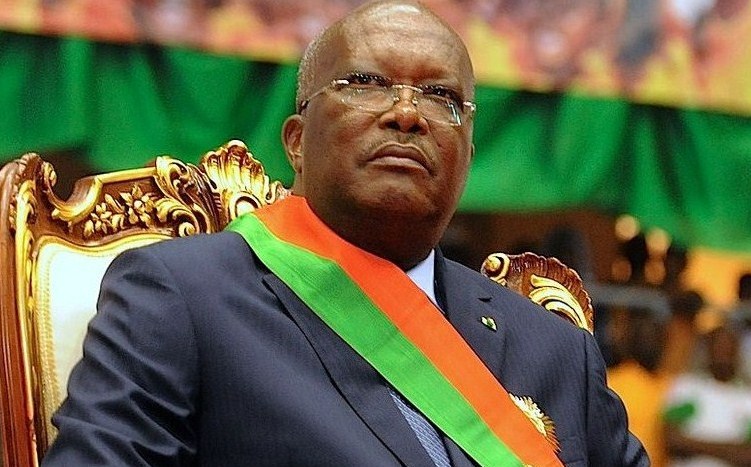

The election of Roch Marc Christian Kaboré as the new president of Burkina Faso on November 30th, which ended 27 years of autocratic rule in this Western African nation, was just one of several political developments that made 2015 a milestone in democratic advancement in Sub-Saharan Africa.

When Kaboré took the oath of office on December 29, he was only the second president the people of Burkina Faso have known in 28 years after his predecessor, Blaise Compaoré, came to power in October 1987 following a coup in which his friend and comrade-in-arms, Thomas Sankara, was killed.

According to the Independent National Electoral Commission, Kaboré secured 53.5 percent of the votes, against 29.7 for his immediate adversary, former Finance Minister Zéphirin Diabré, with twelve other candidates splitting the rest of the votes. Having scored more than 50% plus one votes, Kaboré, formerly speaker of the National Assembly, won without a run-off. Saidou Compaoré, president of the African civil society’s international observers who coordinated the actions of the various observers’ teams told The African:

“It was a credible, convivial campaign that led to the first truly democratic presidential and legislative elections in the history of Burkina Faso.”

Kaboré‘s election came a little over one year after the unexpected October 31, 2014 ouster of former president Blaise Compaoré. Just as the Burkina Faso lawmakers were poised to vote on Thursday, October 30th on a plan put forth by the government of President Blaise Compaoré to allow him to change the constitution to stand for re-election again in 2015—28 years after he came to power in the aftermath of a coup—tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets in Ouagadougou, the capital, and Bobo Dioulasso, the second largest city, to violently protest the move.

Despite the heavy security forces posted at the main intersections of Ouagadougou and in front of the parliament building, protesters stormed the parliament building which they set on fire, and ransacked the residences of some high-level government officials and looted computers and other materials, smashing vehicles, among other things. The announcement, later, by the country’s communications minister, Alain Edouard Traoré, that the government had dropped the plan to amend the constitution, did little to stop the violent uprising. The protesters demanded President Compaoré’s immediate resignation. Compaoré had no choice but to flee to neighboring Cote d’Ivoire the next day.

Eleven months later, the interim government that followed Compaoré’s ouster was the subject of a coup by elements of the presidential guards who remained loyal to their former boss. Thanks, however, to the unequivocal condemnation and physical involvement of regional leaders such as Benin president Yayi Boni and President Macky Sall of Senegal, and the regular army’s continued support for the interim government, the coup was overturned days later.

Kaboré’s election is full of symbolism. Not only is he the second president of the country in 28 years, he is also the first president of this nation with a troubled political history to ascend to the presidency through election since 1966, the year Gen. Sangoulé Lamizana succeeded the country’s first president, Maurice Yaméogo, following massive national protests. Kaboré’s election also legally turned the dark page of Compaoré being one the remaining African heads of state who have been in power for decades. Finally, Kaboré broke another Burkina Faso’s record by being the only non-incumbent president since Maurice Yaméogo to be elected to the high office. Unlike Compaoré’s four elections, all of which were allegedly rigged, Kaboré rose to the president following the first fair and transparent election in 28 years.

But he is no stranger to Burkina Faso’s politics. He previously served as the country’s prime minister and lastly as the speaker of the parliament, and was, ipso facto, very close to former president Compaoré. But the two men split two years ago and Kaboré joined the opposition.

South of Burkina Faso’s borders, the re-election of Cote d’Ivoire’s president, Alassane Ouattara, for a second five-year term on October 25 is on track to end the socio-political chaos that has continuously shaken one of the largest economies in West Africa since the demise of the country’s founding father, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, on December 7th, 1993.

President Ouattara received 84 percent of the votes, against 9 percent for the second-place finisher, Pascal Affi N’Guessan, who ran as one of the rival factions of former president Laurent Gbagbo’s Ivorian Popular Front. By mastering 84% of the votes at the first round, Ouattara, who only needed 50% plus one votes to win, clinched victory without a run-off. But this came really as no surprise to anyone familiar with the Ivorian political theater, given that Ouattara was the heavy favorite months ahead of the incident-free election.

You may also want to read: Alassane Ouattara favored to win easy re-election amid heightened tension

“Incident-free” sounds like a new word as far as Cote d’Ivoire’s political lexicon is concerned, if one looks back at the following political landmarks: the coup staged in December 1999 by a group of young soldiers who gave power to retired Gen. Robert Guéï; the violent protests leading to hundreds of deaths in the wake of Gbagbo’s ascend to power following a bogus election from which key political leaders including Ouattara were banned by Guéï; or Gbagbo’s divisive politics that led to the September 2003 violent uprising that split the country in two, causing hundreds of death, not to mention the short civil war that claimed 3.000 lives in early 2011 upon Gbagbo’s stubborn refusal to accept the crystal-clear election results until he was bombed out three months later from the presidential palace where he hid.

Not everyone in Cote d’Ivoire accepted the result of the October 25 election that gave Ouattara another five-year mandate. Several members of the opposition, including PDCI icons such as former foreign minister Amara Essy and fomer prime minister Charles Konan Banny, as well as the speaker of the Ivorian parliament under former president Gbagbo, head of the LIDER party, Mamadou Koulibaly, dropped out of the race saying that the stage was set for the vote to be rigged. All gave proofs of their claims which were dismissed by the electoral commission as unfounded.

You may also want to read: Former Ivorian prime minister Charles Konan Banny drops out of the presidential race

After less than a full five-year term, Ouattara can boast an impressive economic legacy with an average of 7% annual economic growth since 2012, and for turning Abidjan into a vast construction site, with new hotels and new real-estate developments popping all over town. However, the fruit of his administration’s economic prowess has not so far benefited a large segment of the population, just as, despite the unquestionable social appeasement, discontent has grown over the one-sided justice that has so far spared those on Ouattara’s side who were also responsible for the post-election violence of 2011. “It would be unwise to expect the president to tackle all those biting problems, which have piled up over the years, in just one term,” Fofana Coulibaly, a local wealthy businessman, told The African in a phone interview conducted the day following Ouattara’s re-election. The president vowed, during the campaign, to address those issues head on.

Yet another signal of democratic advance in Africa in 2015 came out of the most populous country with the largest economy on the continent: Nigeria,

If President Obasanjo’s swearing-in on May 29, 1999, which signaled the return of democracy to Africa’s most populous (now wealthiest) nation, was hailed as a historical landmark in Nigeria’s modern history, the democratic and peaceful election of Muhammadu Buhari brings enormous hope to Nigeria, the African region as a whole and, without pushing it too hard, the whole world in many ways.

Most serious presidential contenders are confident they will win. Former Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan who ran under the banner of Nigeria’s main political party, the People’s Democratic Party, which has dominated the political scene since 1999, apparently had no doubt—and indeed repeatedly said—he’d win. While he may have been caught by surprise by his defeat, many observers of Nigeria’s politics expected that outcome.

You may also want to read: In hope Buhari inspires others

In a post-election interview on April 5 with The Punch, a leading Nigerian newspaper, the emir of Kano, Lamido Muhammad Sanusi II, blamed Jonathan’s defeat squarely on the level of poverty in the areas that have cast their votes against the incumbent president, as the culmination of a process that took several years in the making. Said the royalty:

“I believe more and more of those states began to feel that sense of not feeling the federal presence and not feeling the impact of democracy in their pockets and I think it is extremely important for people to connect with the government and when you have such conditions after 16 years of democracy, it was natural that people would want to have a change and I think this is basically what has happened.”

In his inaugural speech, President Buhari who campaigned on the general theme of change—now a common theme in presidential campaigns throughout the world, from Abdoulaye Wade’s sopi slogan in Senegal to Obama’s campaign theme of change—vows to tackle this daunting issue by saying:

“With depleted foreign reserves, falling oil prices, leakages and debts, the Nigerian economy is in deep trouble and will require careful management to bring it round and to tackle the immediate challenges confronting us…”

Nigeria, with a population estimated at 178,516,904 as of July 1, 2014, and with its economic might, has always been a formidable giant in the entire African region, and a partner that developed nations, including the United States, reckon with.

You may also want to read: Obama meets with new Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari

Despite the apparent desire of both Abuja and Washington to maintain good relations, there have been a few bumps on the road over the past couples of years, starting with the Nigerian people’s and some of their leaders’ sharp criticism of what many of them perceived as President Obama “snubbing” them by his decision not visit Nigeria during his first visit to Africa in 2013, and the second, for that matter. But things got more complicated than that, owing to the United States’ exasperation over the high level of corruption in the Nigerian army and across the Nigerian government, and President Jonathan’s perceived reluctance to deal with it. That is not to mention the Obama administration’s frustration over Jonathan’s nagging reluctance to take on the terrorist group Boko Haram. Abuja, for its part, was reportedly terribly upset over the United States’ reluctance to share some key intelligence.

You may also want to read: John Kerry heads U.S. delegation at President Buhari’s swearing-in

Nigerians as well as foreign nationals in attendance at the swearing-in ceremony at Abuja’s Eagle Square noted the large section President Buhari has devoted in his speech to his resolve to crush the Boko Horam insurgency. And the president, thanks to international collaboration, has tangible results to show for his resolve. Despite continued attacks, the terrorist group has been largely diminished, with thousands of kidnapped people freed by the army, while displaced people are gradually returning to their homes.

In many ways, the significance of Buhari’s election transcends Nigeria’s borders.

The fair and peaceful election of Buhari, an opposition leader who was profusely outspent by an opponent who ran on the platform of the party that has won the country’s past three presidential elections, brings hope to an African region where democracy is still in short supply. Johnnie Carson, senior advisor at the U.S. Institute of Peace and a fellow at Yale University who served as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs during President Obama’s first term, and also as U.S. Ambassador to Kenya, Uganda and Zimbabwe, urges the Obama administration to seize the opportunity:

“Nigeria is so important, and the administration should not miss this opportunity to engage with Nigeria’s new government.”

The veteran diplomat also says:

“Strong support for Nigeria will help strengthen its democracy, support its economic growth and enhance its security and stability. An economically vibrant and democratically robust Nigeria is in the interests of Africa, the U.S. and the broader global community.”