Pilgrimage to Goree

By Soumanou Salifou

Gorée is a small island two miles away from Senegal’s capital, Dakar. The uninhabited island was discovered by the Portuguese in 1444 while en route to the Indies. The Portuguese later abandoned the island for internal political reasons, but it remained a port of call frequented by trading boats of various European nationalities. The Dutch took over the Island in 1588 and dubbed it “Goe-ree” (good harbor). In 1627, they bought it and fortified it to protect their commerce, mainly slave trading.For the Europeans, Gorée was coveted because it offered a safe mooring in a convenient location off the coast of the new West African trading territories. The Portuguese, the French, the Dutch and the British fought over the Island until the Count d’Estrée took it for France in 1677.

Gorée quickly grew in stature, being the first anchorage at which ships from Europe, and later transatlantic traffic, stopped. The European trading companies built warehouses on the Island to hold the guns, salt, cloth and other items that they bartered with the African tribal leaders for gold, hides and, above all, slaves.

As sugar-cane cultivation spread into the Americas, the need for labor on the plantations rose sharply. The slavers bartered with the local chieftains for what was cruelly called “black ivory”– slaves. The sinister trade began in the mid-15th century and went on for more than 300 years during which more than 20 million able-bodied black men, women and children, chained at the ankles and neck, were transported to Gorée to be sorted out and imprisoned as they waited for shipment to the plantations across the Atlantic.

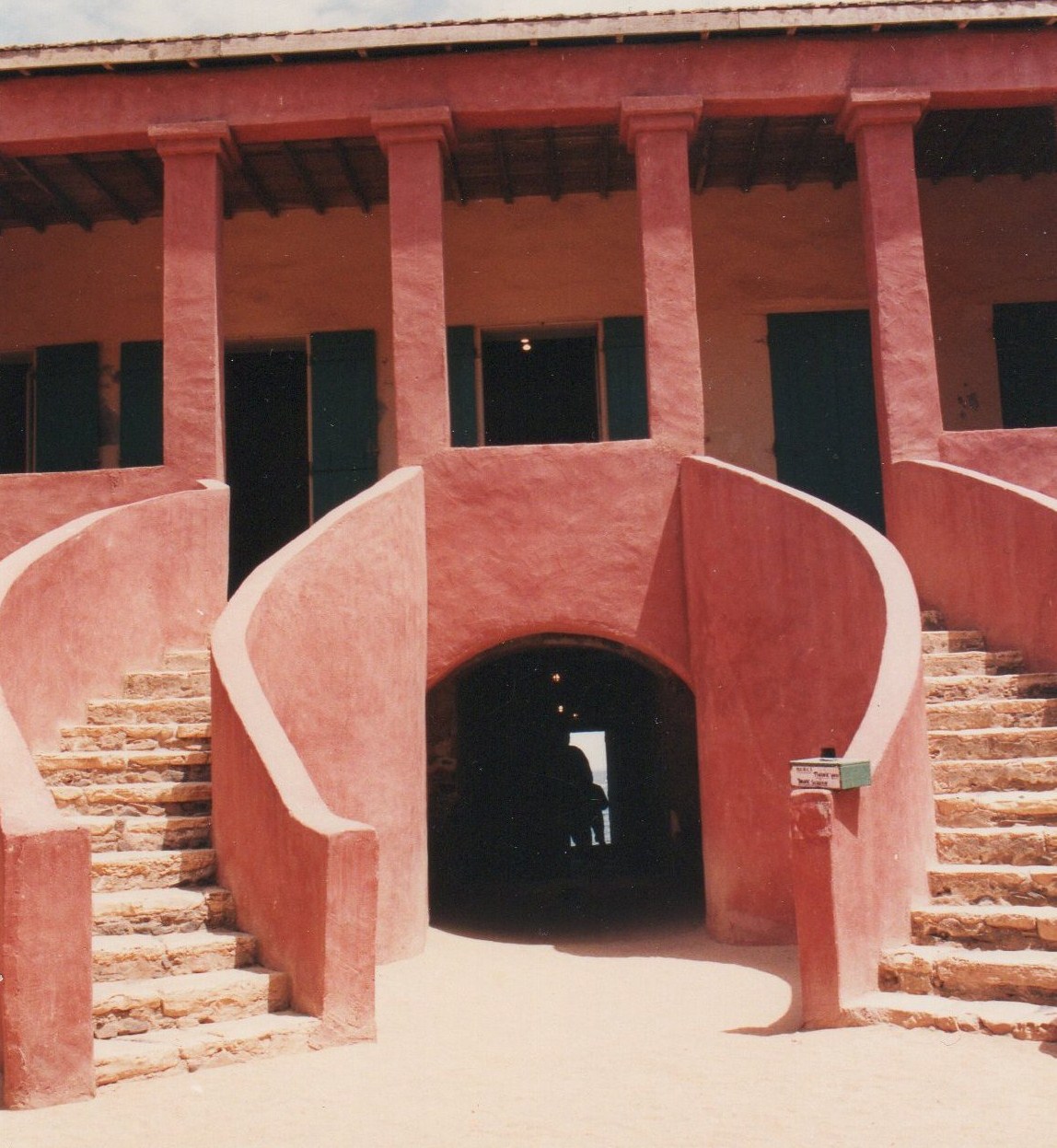

A pilgrimage of The African to Gorée started at what, at least for black people, is the most significant place of all on the Island: The Slaves’ House Museum.

A big step into the past

The three-decked ferry taking us to Gorée was almost full to capacity 20 minutes before departure time. The majority of the three hundred or so passengers were Europeans, but there were also a few Asians and a fairly large number of Senegalese and other Africans. At the end of the 20-minute voyage, as soon as we set foot on the concrete quay which replaced the original wharf made from tree trunks in the 19th century, my photographer and I rushed to the Slaves’ House Museum built some time between 1780 and 1784. Halfway to the Museum, we met its director for 30 years, Joseph Ndiaye, who pointed out the historical significance of the Museum: “Jewish concentration camps lasted for about ten years, but slavery went on for 350 years and yet nobody talks about slavery!” he complained. Mr. Ndiaye sounded somewhat relieved when he added that he is often invited outside Africa to talk about Gorée. He mentioned specifically his invitations to Boston University.

Read the full story in The African.