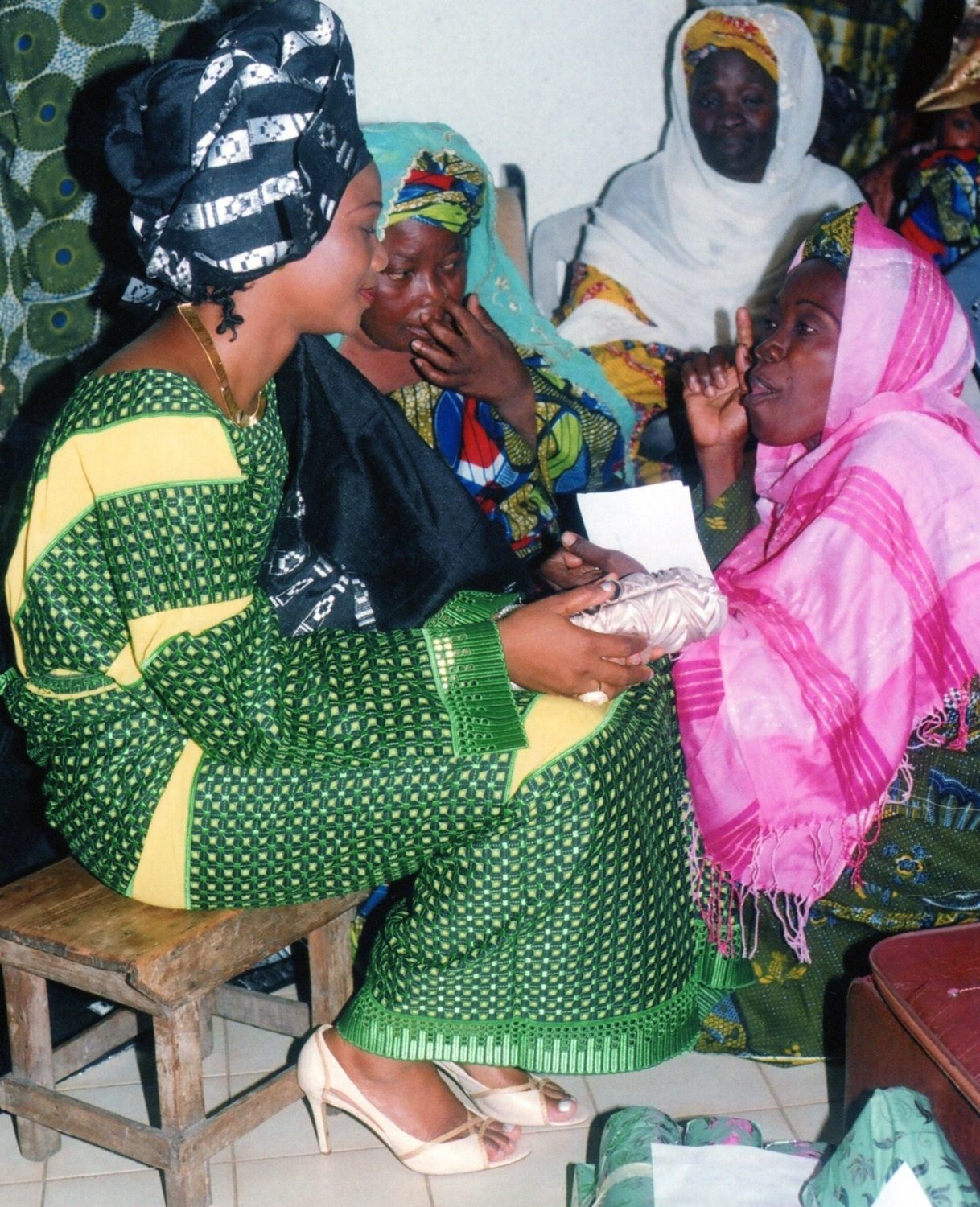

A dowry ceremony in Benin

By Amina Sidiki

Sofia Aly (maiden name Salifou), 33, an accountant, got legally married a couple of years ago to Osséni Aly, a bank employee. Soon thereafter, they had a baby-girl. The couple got married with the full knowledge and consent of both families, but, for some reason, skipped the dowry ceremony – a traditional ritual consisting in the groom giving various items to the bride’s family to “ask for their daughter’s hand” (to marry her) as the expression goes.

Traditionally, the dowry used to be an integral part of the wedding ceremony in probably all African societies. But the monetary value of the items required by the groom’s family – cows, goats, textile, jewelry or lesser-value items – and the cash that came with those items, varied (and still does) from one social group to another, and even from one family to another, as did the very nature of the dowry ceremony itself. Though a little dated – especially in urban areas – like many other centuries-old practices, the dowry ceremony is still alive in families with rural roots, such as the Salifous whose roots go back to Cana, Southern Benin, once the spiritual city of the mighty kingdom of Dahomey, now just a big village.

Around 10 on a sunny Saturday morning of April, a group of about twenty men and women representing the family of Sofia’s husband walked into the Salifou family’s sea-side home in Cotonou, Benin, carrying various items on their heads, singing cheerfully and praising the Salifou family. One of the men held a rope tied to the neck of a goat. Osséni Aly was noticeably (and intentionally) absent.

By then, about sixty members of the Salifou family had gathered in the ground-floor level of the Salifou’s residence, most of them wearing their best attires. But two influential members of the Salifou family deliberately stayed upstairs, in-keeping with an age-old protocol that required that they show up only after the groom’s envoys had been seated. One of the two men, Sofia’s paternal uncle and the latter’s cousin (in this family as in several other African families, cousins are referred to as brothers, so both men are the paternal uncles of Sofia, whose father died almost a year earlier).

The groom’s family members were seated facing the bride family’s VIP couch, with the representatives of the bride’s maternal family on the latter’s left, and the rest of the Salifou family members seated on the right of the VIP couch. By now the two influential family members had joined the rest of the people downstairs.

A member of the groom’s family came forth, knelt down and spoke in a voice that, though clear and loud enough to be heard by all, showed a high degree of humility and politeness. He said: “We have seen a tree in your backyard that we know will bear very good fruit. Knowing that we cannot eat that fruit without your permission, we have come this morning with humility and respect to ask your permission.” Then followed what seemed like an awkward silence quickly broken by cheers and a song by the representatives of the groom’s family.

Then, with one knee still on the hard floor, the man listed the items the groom’s family has brought and to whom each item goes. For the bride: A nice leather suitcase (presumably containing clothing); two large, decorated imported metal containers known as paavi that African women value; a bag of salt (essential for cooking) and the sum of 50,000 CFA francs (about $100). For the bride’s father: 10,000 CFA francs (about $20) plus a 12-yard piece of textile and liquors. For the bride’s mother: 5,000 CFA francs (about $10) plus a 6-yard piece of textile and liquors. For the paternal in-laws: 10,000 CFA francs plus liquors. For the maternal in-laws: 10,000 CFA francs plus liquors. For the extended in-laws on both sides: 5,000 CFA francs plus cola-nuts. For the bride’s paternal aunts (who were essential to the organization of the dowry ceremony): 5,000 CFA francs. For the young men who live in the neighborhood: 2,000 CFA francs (about $4. Traditionally, in a typical rural setting, young men are the ones responsible for security in the area and must be acknowledged by visitors). Besides the salt and the suitcases, all the items were elegantly wrapped up.

After yet another song and cheers from the groom’s corner, one of the bride’s aunts said, faking to be mean, in an effort to comply with the required tradition, that she was not sure the items brought by the groom’s family were genuine. “The paavis look fake; and I am not sure those bottles of liquor actually contain liquor. They might just be bottles of water.” She then added: “By the way, there is a bottle of Gin missing. You’d better get your act together, people.” Another aunt sitting next to the first one spoke in a soft manner that did not veer toward hyperbole like the previous aunt and said that the background of the groom’s family spoke favorably for them.

Then a female member of the groom’s family came forward and informed the audience that indeed a bottle of Gin was missing, but said it was not intentional. She added that an order had just been placed for that bottle, and delivery, by airplane, was expected imminently. Five minutes later, the same lady produced a naked bottle of Scotch Gin, not without specifying that “it came from Washington, D.C., Barack Obama’s town.” And the crowd broke into cheers and applause.

“Do you really know your woman, the one you have come here for today?” asked the fakingly mean aunt. “Yes, we do,” the groom’s family said. “Let’s see if you really do,” the aunt added. Then, one after the other, three women faking to be Sofia paraded in front of the groom’s family who literally booed them, giving 1,000 CFA francs (about $2) to ask each to get lost. After a few moments that looked like an eternity, Sofia came out, dressed in expensive traditional attire and wearing a massive-gold chain, glowing with beauty. The groom’s corner cheered her and the rest of the audience joined in.

Sofia sat on a stool next to the aunts as required by tradition. At which point one of the aunts said, pointing to the items sitting on the floor: “These are the things these people have brought. I don’t like the stuff.” The audience burst out laughing and Sofia, as if really hurt by the remarks, had an uncomfortable smile on her face. After the laughter died down, Sofia said “But I like the things,” sending the audience in a long, loud laugh.

The nice paternal aunt took charge and officially accepted the dowry. The other aunts joined in and sealed off the ceremony. Then followed a pretty long session of advice to Sofia as to how to keep her marriage alive and strong forever.

A spokesperson for Sofia’s maternal family blessed the marriage (while Sofia’s only maternal uncle broke into tears over the absence of Sofia’s mother who had died more than a decade earlier). The uncle finally recovered and in turn blessed the marriage. Then the paternal aunts spoke, wishing the couple well and stressing that their daughter must be treated with respect, must respect her husband and behave on the principle that marriage is for life.

Then, the oldest person in Sofia’s paternal family, the very owner of the house – one of the two VIPs – spoke in an intentionally-low voice that carried a balanced blend of authority and dignity, a voice so low his words were repeated by the second VIP. He thanked the groom’s family for finally complying with the dowry tradition and congratulated his “daughter,” the bride, as well as the groom (through the latter’s family). “Marriage is a strong tie between two families, and the tie must be nourished on a permanent basis,” he said. He advised the bride to abide by the high moral principles she was taught by her parents, which include respect, selflessness and tolerance. He finally wished them well. Another male relative who goes by the nickname of President spoke along the same line and stressed the need for the couple to strictly practice their religion. Finally, another uncle who lives in the United States and who goes by the nickname “Tonton Américain” (American Uncle) said that while money is important, the couple should never let money come before love. “When you are bound by genuine love, even when you are low on cash, your marriage survives and you get a chance to stay together and overcome the money crunch,” he stressed.

The various items brought by the groom’s family were given to the individuals they were destined for. A several-course lunch was served, but only after the groom’s family had left with plenty of food cooked for them by the bride’s family, for it would be a scandal for the groom’s family to eat in the presence of their in-laws the very day the family “officially gave” them their daughter.