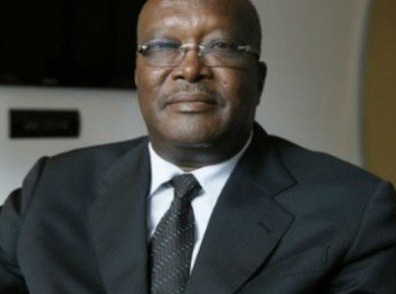

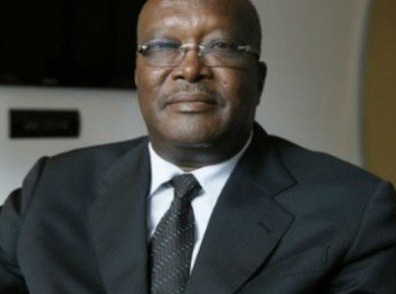

Kaboré’s election as new Burkina Faso’s president signals democratic strengthening in Africa

BY JIBRIL TURE

The election of Roch Marc Christian Kaboré as the new president of Burkina Faso on November 30th signaled the strengthening of democracy not only in Burkina Faso, but in the Sub-Saharan region as a whole.

When Kaboré takes the oath of office, he’ll be only the second president the people of Burkina Faso have known in 28 years after his predecessor, Blaise Compaoré, came to power in October 1987 following a coup in which his friend and comrade in arms, Thomas Sankara, was killed.

According to the Independent National Electoral Commission, Kaboré secured 53.5 percent of the votes, against 29.7 for his for immediate adversary, former Finance Minister Zephirin Diabré, with twelve other candidates splitting the rest of the votes. Having scored more than 50% plus one votes, Kaboré, formerly speaker of the National Assembly, won without a run-off. The president elect, who stated his awareness of he “weight” of the presidency and the responsibility that comes with it, said his first priority will be to put his people to work.

Kaboré‘s election came a little over one year after the unexpected October 31, 2014 ouster of former president Blaise Compaoré. Just as the Burkina Faso lawmakers were poised to vote on Thursday, October 30th on a plan put forth by the government of President Blaise Compaoré to allow him to change the constitution to stand for re-election again this year—28 years after he came to power in the aftermath of a coup—tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets in Ouagadougou, the capital, and Bobo Dioulasso, the second largest city, to violently protest the move. Despite the heavy security forces posted at the main intersections of Ouagadougou and in front of the parliament building, protesters stormed the parliament building which they set on fire, and ransacked the residences of some high-level government officials and looted computers and other materials, smashing vehicles and other materials. The announcement, later, by the country’s communications minister, Alain Edouard Traoré, that the government had dropped the plan to amend the constitution, did little to stop the violent uprising. The protesters demanded President Compaoré’s immediate resignation. Compaoré had no choice but to flee to neighboring Cote d’Ivoire the next day.

Eleven months later, the interim government that followed Compaoré‘s ouster was the subject of a coup by elements of the presidential guards who remained loyal their former boss. Thanks, however, to the unequivocal condemnation and physical involvement of regional leaders such as Benin president Yayi Boni and President Macky Sall from Senegal, and the regular army’s continued support for the interim government, the coup was overturned days later.

Kaboré‘s election is full of symbolism for Burkina Faso and the rest of Africa. Not only is he the second president of the country in 28 years, he is also the first president of this nation with a troubled political history to ascend to the presidency through election since 1966 when Gen. Sangoulé Lamizana succeeded the country’s first president, Maurice Yaméogo, following massive national protests. Kaboré‘s election also legally turned the dark page of Compaoré being one the remaining African heads of state who have been in power for twenty years or more. Finally, Kaboré broke another Burkina Faso’s record by being the only non-incumbent president since Maurice Yameogo to be elected to the high office. Unlike Compaoré‘s four elections, all of which were allegedly rigged, Kaboré rose to the president following the fair and transparent election in 28 years.

But he is no stranger to Burkina Faso’s politics. He previously served as the country’s prime minister and lastly as the speaker of the parliament, and was, ipso facto, very close to former president Compaoré. But the two men split two years ago and Kaboré joined the opposition.

Kaboré won the election with a clearly high score and a large number of seats in parliament but not the majority. He therefore will have to share power with other parties in the legislative body.