The king of Cana launches a 57-day centennial celebration

BY LOU SIFA

IMAGES BY ARSENE KASSEGNE

Bracing the biting dry heat and the stubborn thin dust of the Harmattan season, a colorful and vibrant crowd of royalties from around the Abomey area, elected officials, religious leaders, passionate kings’ care-takers, more than one thousand cheering Cana residents and other guests from near and far attended a day-long special program on January 8 at the royal palace of Cana as part of a 57-day celebration of the centennial of His Majesty Togongon Langanfin Glèlè, the late king of Cana. The historical event was initiated and hosted by the late king’s son and reigning monarch, Dada Aïhotogbé Langanfin Glèlè.

King Dada Aïhotogbé Langanfin Glèlè’s arrival at the palace this January 8 was quite an event in itself. The beautiful traditional music coming out of the loud speakers on the premises gave way to the no-less-loud music of the dozen-piece live band playing ahead of the king and his immediate entourage, all clad in the fabric made especially for the occasion. The monarch, comfortably seated in his hammock carried by four men, wrapped himself in a large piece of white cloth with royal designs, wearing a couple of long necklaces and other royal apparel, but had no shirt on. Shaking the recade (royal baton) that he carried in his right hand, he warmly greeted his visibly-excited subjects with a broad smile while a group of about two dozen women sang his praises in what sounded like a fine, well-rehearsed song. It all came together beautifully like a well-choreographed show, in the age-old tradition of the sophisticated Danxomê kingdom, blended in a glory of light, pinkish dust.

Despite defeating the Danxomê kingdom whose resilient army put up a ferocious fight from 1890 to 1894 in its resistance to colonization, the French colonial power, even after annexing the territory known today as the Republic of Benin into French West Africa in 1894, proved quite nervous. Not only did the new masters deport the defeated king, Gbêhanzin, to Martinique and let him die in exile after replacing him with his brother Agoli-agbo; six years later, they also deported Agoli-agbo to Gabon, for fear, Dada Aïhotogbé Langanfin Glèlè, Gbêhanzin’s nephew and the current king of Cana, tells The African, “of the continuation of royal practices on the Abomey plateau.”

Eventually, the colonial administration created new administrative units called “canton” across the remains of the kingdom—though none in Agbomê itself—that they filled with the natives. Thus, Langanfin Glèlè, King Gbêhanzin’s brother, was appointed chief of the “canton” of Cana on December 25th, 1916.

France’s nervousness about “the continuation of royal practices” were doomed, as it were, as Langanfin became the king of Cana in the process under the name Togongon Langanfin Glèlè, and proved a staunch promoter of the local values and tradition. [Togongon, in the local language, Fon, means deep well].

In his keynote speech during the launch of the centennial celebration on January 8, Cyriaque Agonkpahoun, president of the centennial’s organizing committee, had nothing but praises for the late king. “Our dignity as children and descendants of our forefathers lies in our ability to defend and nurture our values,”

he stated, adding: “Before the tribunal of history and in the courtroom of our ancestors, we’ll be judged on the basis of our roles in the affirmation of our identity, the safeguarding of our heritage, and the continuation of the actions of our brave and audacious guides who, in the past, showed us the way to the future.” Agonkpahoun, a high-level civil servant, went on to say that the late king, who was, along with his brother Gbêhanzin, a member of the inner-circle of their father, King Glèlè, was a role model during his lifetime and has remained so even after his death. “Togongon Langanfin Glèlè not only worked hard to maintain the vestiges of the kingdom and the work of our ancestors in the Cana ‘canton,’” Agonkpahoun said, “he also worked hard for the unity of the royal families and their descendants.”

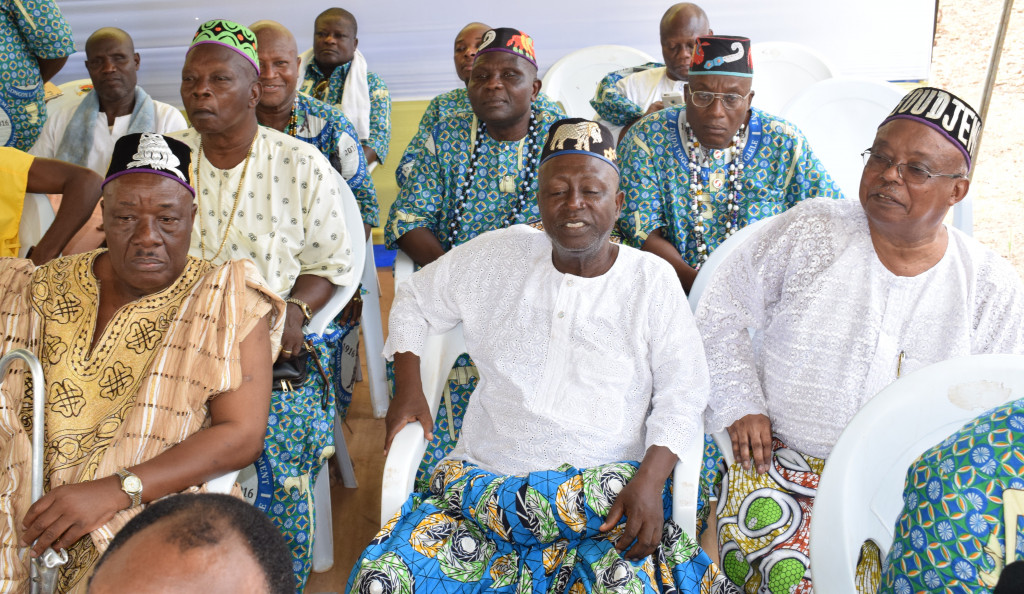

From left to right: Dah Dessou and Dah Goudjèman

King Dada Aïhotogbé Langanfin Glèlè’s rise from his seat to address his subjects and his guests caused quite a stir, with the crowd, including the officials seated around him, and his subjects cheering him, and the praise singers doing their thing, and the music exploding.

In his speech delivered in Fon, the kingdom’s native language and the main language in Benin (though he speaks perfect French), the monarch said: “We, the children of my father Dada Langanfin Glèlè, have decided to honor his memory and show the Cana residents that Cana is the alpha and the omega [the beginning and the end] of the Agbomê kingdom.” The king later elaborated on this subject in an exclusive interview with The African.

The centennial celebration is a 57-day-long affair that started on December 25th, the exact day of the 100th anniversary of the late king’s appointment as chief of the Cana “canton” by the colonial administration. In-keeping with the kingdom’s tradition, prior to officially launching the ceremony on January 8, King Dada Aïhotogbé Langanfin Glèlè had to be granted permission by his ancestors in a

ceremony called Gbébiobio (permission request) in the late king father’s palace at Djako in Cana. Several other essential rituals include workshops with the kingdom’s voodoo chiefs; a ceremony honoring the memory of the kingdom’s famous female warriors, the amazons; and houékplokplo, aimed at “purifying” the palace.

Most of these rituals, not unlike the January 8 official launch, provide the occasion to exhibit a sampling of the kingdom’s rich music and dances, with their immense beauty that makes even non-natives want to join in.