Beninese fear their democracy may soon be under attack

BY LOU SIFA

(Updated on 2 June.)

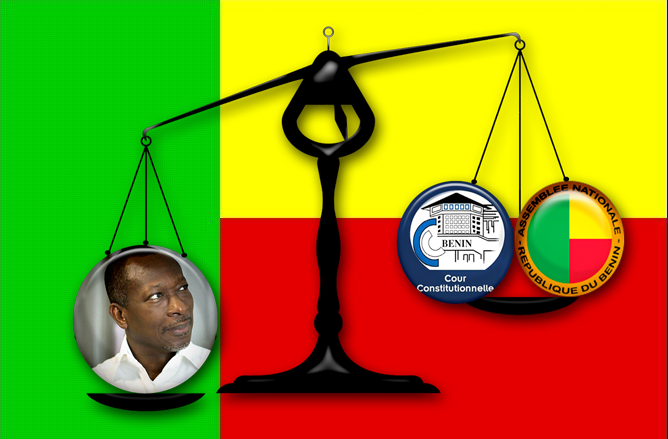

Checks and balances—a notion rooted in the separation of powers to ensure no one branch of government has too much power to be able to control another—are one of the pillars of the foundation on which Benin’s vibrant democracy—if flawed in some ways—has rested since the French-speaking West African nation embraced the rule of law 28 years ago. But the Beninese people now fear that is about to change, and are crying foul.

The Constitutional Court, the backbone of checks and balances

Benin’s Constitutional Court, as its very name indicates, is the guardian of the nation’s constitution. It carries out its duties in small and grand ways to uphold the country’s fundamental law.

For religious reasons, when taking the oath of office in April 1996, then-President-elect Mathieu Kerekou, a born-again Christian, intentionally avoided reciting the phrase prescribed by the Constitution as part of the oath: “the spirits of the ancestors.” After a citizen filed a petition with the Constitutional Court stating that Kerekou thus broke article 53 of the Constitution, the president was required by the court to take the oath again, which he did.

Just this past 18 January, the court ruled unconstitutional a new law adopted by the National Assembly that denied the right to go on strike to judges, health workers, and para-military personnel. The piece of legislation, introduced by the Talon administration, aimed to avoid the all-too frequent work stoppage in the judiciary sector; the loss of lives in the nation’s hospitals due to health workers’ sometimes lengthy strikes; and the citizens’ security being jeopardized by paramilitary personnel such as firefighters being on strike.

Several previous rulings by the court were also unfavorable to the Talon administration. They include the ruling with the docket number DCC 16-091 dated 7 July 2017 about the manner in which the acting managing director of the state-owned Radio & Television station was appointed, which the court ruled unconstitutional, saying it violated the organic law of the High Authority for Audiovisual and Communication. There was also the case with the docket number DCC 17-251 dated 5 December 2017 relative to the executive branch’s plan to take legal action against two Beninese citizens accused of causing the loss of 125 billion francs to the cotton sector, without giving the accused a chance to be heard by the organization that conducted the audit leading to the government’s decision. A case, the court ruled, of the violation of the defendant’s rights and the principle of all citizens being equal before the law.

The Talon administration, not unlike administrations anywhere, felt these rulings were slaps in its face. But it’s expected to have its way soon.

The president’s man soon in control

The second five-year mandate of the men and women respectfully referred to as ‘the seven wise’ who make up the Benin Constitutional Court is coming to an end in June. Their replacements—four appointed by the parliament, and three by the executive branch—are already known, and are on stand-by to take charge. The man expected to lead the new court is a lawmaker and senior minister in charge of Justice, Joseph Djogbenou.

Djogbenou, 49, holder of an agrégation, the highest academic degree in the French educational system, is a high-power legal icon. He was an influential member of the civil society who, after being elected to parliament three years ago, easily won the prestigious position of chairman of the Judiciary Committee.

Djogbenou was also President Talon’s lawyer when the president was sued back in 2012 by his one-time friend and protege, then-President Yayi Boni, who accused Talon of attempting to poison him and of plotting a coup to overthrow him. This came after a surreal story alleging that Talon had fled Benin in a car trunk to a neighboring country and caught a plane to France to avoid being arrested by Yayi. (A lower court dismissed the case, which was later upheld by a higher court, leading to Yayi’s failed request that the French authorities extradite Talon to Benin).

The bonds created between Djogbenou and his client by these dramatic developments grew stronger throughout the 2016 presidential campaign season. Djogbenou, whose party campaigned for Talon, was appointed Senior Minister in charge of Justice following Talon’s victory in April 2016.

Djogbenou, visibly the most vocal member of Talon’s cabinet—beyond and above the role of the administration’s spokesperson that he is—acts routinely like the administration’s “defender-in-chief” on all kinds of issues, including highly-controversial ones such as the administration’s banning, last year, of university students from holding meetings and demonstrations on the Abomey Calavi campus, and their brutal beating that ensued; the recent handling of a lawmaker accused of wrongdoing who, after turning himself in and being let go by the judge, was beaten by the police, taken to a hospital for treatment, only to be later thrown in jail. Djogbenou is on the record for making inflammatory statements following the rejection, in April 2017, of President Talon’s planned revision of the Constitution.

Owing to the minister’s track records and personality, members of the Benin elite fear he would not be an impartial constitutional court’s president.

Citizens raise hell

In Benin, a small country of only 11 million people, the social media appears to be among the busiest and most qualitative in Sub-Saharan Africa, with chat groups buzzing with political analyses of all kinds—if largely partisan like elsewhere. So the prospects of Djogbenou becoming the next president of the country’s Constitutional Court has been the talk of the nation for most of the past two weeks.

Even before the minister was appointed on 16 May by the parliament as a member of the next court, many, especially in the media and the legal and paralegal circles, had criticized the Talon administration for not complying with the rulings of the Constitutional Court. In an article previously published in one of the leading local newspapers, La Nouvelle Tribune (and later posted online on 13 December 2017) with the title The Constitutional Court decides, Talon resists, Rufin Noudofinin, a legal consultant, showed how in twenty months Talon has shown contempt for the court’s rulings. After a lengthy review of some of the rulings, Noudofinin blasted the administration by stating:

“Once elected president, Talon was expected to be a role model in terms of respect for the Constitutional Court’s rulings. Unfortunately, far from being the best guardian of the constitutional temple, President Talon has become a real defiler. He hates all the rulings of the court that are unfavorable to him.”

In a lengthy post on 21 May in one of the reporters’ chat groups, and looking ahead to the Djogbenou court, Vincent Foly, one of the most sophisticated reporters in Benin, conveys the concerns many in the media have expressed.

This veteran journalist, publisher of one of the leading local newspapers, shows how Djogbenou owes his fast rise in politics in just three years to President Talon, and the minister’s all-out efforts to pay back the president in any way he sees fit, whether by interfering in ongoing legal cases, or making inflammatory statements and saying “I take responsibility” when “his words contradict some of his past actions.” Foly writes:

“In a football game, a referee is supposed to be neutral, not take sides. The credibility of a referee lies in his ability to stay at an equal distance between the two parties in a conflict.”

Folly points to Djogbenou’s younger age compared to the age of previous presidents of the court—presumably a hint to the minister not being as experienced as his predecessors.

The reporter, who acknowledges past Constitutional Courts have not always been impartial in their rulings, is particularly worried about Djogbenou, a man so intimately involvement in the Talon administration.

“How not to be worried about the future of our democracy when we see that the stage is set for this man who, in three years, has piled up bad mistakes, clumsiness and failures, is poised to rise to the helm of the ultimate arbitration institution of our democracy.”

An exercise in futility?

Benin is a battleground of political ideas that sometimes don’t impact real-life politics. Most likely, the persistent criticism that the Talon administration ‘resists’ the rulings of the Constitutional Court, and the wide-spread fear that the Constitutional Court led by Djogbenou would be biased toward the executive branch, will amount to a mere exercise in futility. If indeed Djogbenou is picked by his peers to head the court, the institution would most likely give Talon carte blanche to implement virtually any policy it sees fit. The rhetoric would flare up, but it would be business as usual at the Marina Palace.

Another threat to Benin’s democracy lies in the unconditional support Adrien Houngbedji, the speaker of the parliament, has pledged to the Talon administration. Houngbedji, who openly said his political party, PRD, is tired of being in the opposition, was behind a massive rally staged a few months ago to support the actions of Talon’s government. Click here for more.

With Houngbedji in Talon’s pocket, and Talon’s expected control over the Constitutional Court, the president has control over all the levers of power,” said a senior civil servant to The African, on condition of anonymity, fearing for his job.