Cana, a potential tourist’s attraction overlooked by President Talon

BY SOUMANOU SALIFOU

IMAGES BY ARSENE KASSEGNE

Tourism promotion is one of the features of the Benin Government’s Plan of Action unveiled by President Patrice Talon on December 16. The tourism component of the Plan calls for making Abomey a cultural and artistic showcase to attract tourists. But there is no mention of Cana in the Plan, Cana the one-time holy city of the Danxomê kingdom after which the colonial power named the entire present-day Benin formerly known as Dahomey (the French spelling), in recognition of the kingdom’s heroic resistance to colonization that forced France into a protracted two-year war before breaking the back of the inferior Danxomê army.

Mindful of the spiritual shield of the voodoos housed at Cana on the Danxomê army, writes Jérôme C. Alladayê, a History professor at the National University of Benin in a 1993 essay titled “Cana, the Holy City of Danxomê,” the French army made sure it destroyed those protective forces for the purpose of weakening the enemy.

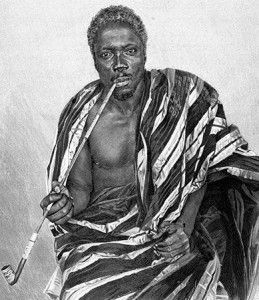

Cana was also the theater of the last battle directed in person by the last pre-colonial king of Danxomê, King Gbêhanzin (1889-1894), against the French colonial army. The final military operations that broke the back of the Danxomê army happened at the Djêhoué Palace built by King Glèlè (1858-1889), Gbêhanzin‘s father. The one-time huge palace built using the sophisticated architectural know-how of the kingdom is now reduced to an empty space. Only part of the famous 4.59 x 9 ft-tall walls called ahoho are now standing.

OTHER ROYAL PALACES IN CANA

The significance of Cana as a prime historical town and a potential tourist attraction also lies in the fact that it is home to six other royal palaces, as each king of the dynasty, from King Agadja down, was required to build his own individual palace in Cana while living in the main palace at Agbomê. Only Gbêhanzin and Agoli-Agbo could not comply with the requirement, as a result of the brutal French invasion. The kings stay at their own palaces in Cana during an annual purifying bath ritual in the Hlan River, among other spiritual functions of their individual palaces.

Agadja (1718-1740) erected his palace at Cana Tota. His son, Tegbesu (1742-1774) built his own (the largest of all) at Cana Daho (The Great Cana) around 1748.

In 1820, Guezo built a majestic palace in Gbangnamê, and personally supervised the erection of a djèho (prayer chamber for the dead) in honor of his father, Agonglo. This palace now houses a mausoleum for each of the twelve kings of the dynasty.

THE EMBASSY OF THE OYO KINGDOM IN DANXOME

From King Agadja (1711-1742) and on, the king of Oyo, in present-day Nigeria, had an ambassador known as Babaedja to the Kingdom of Danxomê. This emissary was responsible for collecting and forwarding to the king of Oyo the tributes that the Danxomê kingdom paid annually to Oyo after losing a war to the Oyo kingdom. Babaedja worked closely with Ayoyitomabou, the Danxomê Ambassador to Oyo, to ensure the safe delivery of the tributes that comprised 41 men, 41 women, 41 guns, 41 barrels of gun powder, 41 packages of textile, 41 baskets of pearl, 41 goats, and more. The embassy operated for nearly a century until King Guezo (1818-1858), who illustrated himself as a ferocious warrior-king, succeeded in freeing the Danxomê kingdom from the tribute payment after winning a series of wars against the then-weakened Oyo kingdom.

The descendants of Babaedja are an important part of Cana today, and very proud of their history. They tell The African their ancestors are the ones who introduced Egungun, the Yoruba masquerade serving as a link between the dead and the living, to the Benin environment. This is now a wide-spread, dominant secret practice throughout the southern region of Benin.

But the Babaedjas are not the only Cana residents of Oyo origin, or, indeed, from parts of present-day Nigeria, that are part and parcel of Cana’s history. Ancestors of the community of Muslims who live near the interstate highway that crosses Cana north-south are from various parts of present-day Nigeria: the one-time Oyo empire in the western and north-central

region, Kano in the north, and more. The oral tradition says that these Muslims served as spiritual advisors to the kings. Though away from home, they kept their religious practice in Cana, and resided not far from King Agadja’a palace at Tota. But, with time, King Agadja was annoyed by their loud early morning calls for prayer and ordered them removed from near the palace and had them placed at their present location at Cana Malê (the Muslim section of Cana) which boasts a decent mosque with a Koranic school.

Though the Oyo empire was Danxomê‘s staunch enemy for as long as historians can remember, and the two states were permanently at war, the Danxomê kings traditionally surrounded themselves with people of Oyo origin, some of whom were actually established in Cana before the arrival of the first Aladoxunu who later founded the Danxomê kingdom. In the words of Dah Wankpo, a member of King Aïhotogbé‘s court, “the purpose was to use these Oyo people’s knowledge in warfare to better fight the Oyo empire.”

“Cana is the alpha and the omega,” (the beginning and the end), the king of Cana, His Majesty Dada Aïhotogbé Langanfin Glèlè, stated repeatedly throughout the three-month celebration of the centennial of his grand-father, the late King of Cana, His Majesty Togongon Langanfin Glèlè, in a quasi-desperate effort to call the authorities’ and the world’s attention to the need to showcase Cana’s contribution to Benin’s overall history. Not to rehabilitate the important history of this significant link in the chain of Benin’s historical heritage is tantamount to letting an entire section of a library burn down, the king emphasized.