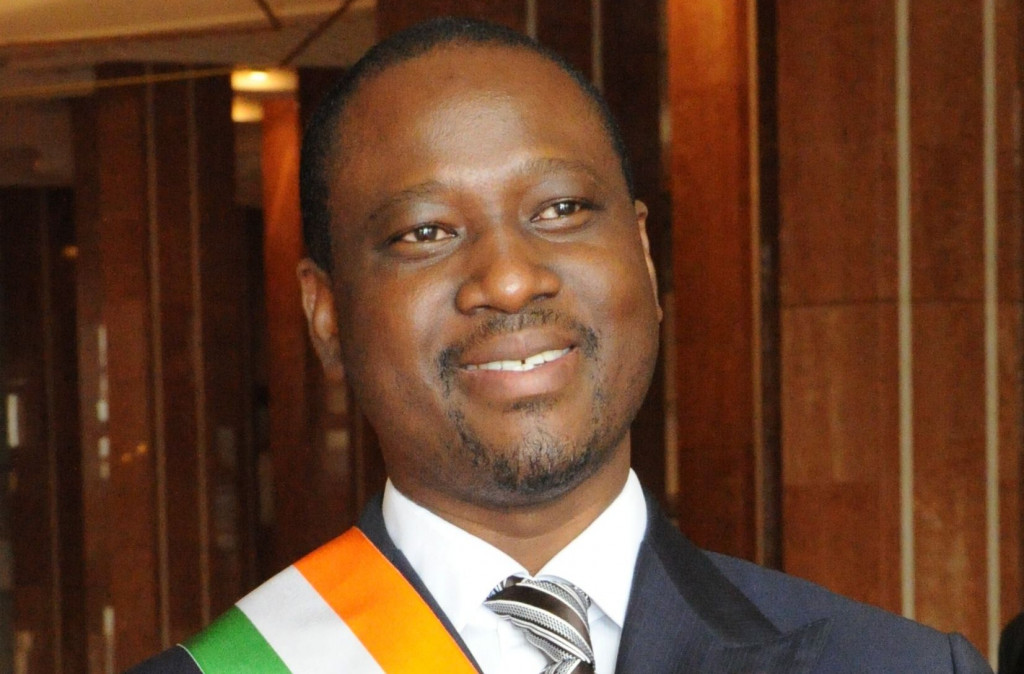

Presidents Ouattara and Soro: the hatchet appears buried

BY JIBRIL TURE

A high-profile meeting between Côte d’Ivoire’s president Alassane Dramane Ouattara and the country’s speaker of the parliament, Guillaume Soro, at the presidential palace in Abidjan on 3 November, 2017 marked the first time the two political giants saw each other eye-to-eye in more than two months. The carefully-prepared meeting followed Soro’s return home on October 22 after a long absence that attested to the lingering tension between the two one-time political allies. Ouattara and Soro had joined efforts to push out former President Laurent Gbagbo who refused to step down though he lost the October 2010 election to Ouattara.

Without really stating the root cause, several credible news reports had persistently mentioned the tension between the presidents, focusing on the mediation of sorts attempted by former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo who was allegedly approached by his Ivorian counterpart to help mend fences with Soro. Prior to seeking Obasanjo’s mediation, President Ouattara had allegedly sought the intervention of the president of the High Council of Côte d’Ivoire’s imams, Cheick Boikary Fofana, not to mention that of Guinea Conakry’s president, Alpha Condé, but still to no avail.

Yet, both Ouattara and Soro denied there was any tension between them. Speaking to the press in Niamey, the capital of Niger, on the heal of the meeting of the Economic Community of West African States, the Ivorian president stated on 24 October: “There’s no crisis between the speaker of the parliament and me.” Soro concurred: “I can assure you that my relationship with the president of the republic is good,” said Soro upon his return home. “I’ll do my best to make sure our relationship remains good. In the next few days, I’ll go see the president of the republic to speak with him.”

In the same remarks, though, the speaker of the parliament also stated: “I have come back to take my rightful place in the political process, to contribute, to the best of my ability, to the political appeasement, contribute to working toward reconciliation and civil peace.” He reiterated: “I call for peace and dialogue.”

As the speaker of the parliament made those remarks at the Abidjan airport on 3 November upon his return, his supporters cheered him chanting ‘President! President!’

Indeed, Soro, the leader of the rebellion movement, the Patriotic Movement of Côte d’Ivoire, that sought to overthrow the government of then-President Laurent Gbagbo in September 2002 but was stopped in the center town of Bouaké by the French troops from going all the way to Abidjan, had long been believed to want to succeed his ally Ouattara at the helm of the country when the current president’s second term expires in 2020.

That prospect has recently been clouded by a number of events.

Soro, duly elected member of parliament under the umbrella of the ruling party, the Rally of the Republicans, did not attend the party’s convention held last September. Furthermore, his protocol director, Souleymane Kamaraté Koné, was recently arrested in connection with an alleged plot while the speaker was out of the country. In an open letter published online on 10 October, the day following his arrest, Koné writes: “I’m in jail today because of my boss Guillaume Soro. I am not the one being targeted.” Asked by the press to comment on the matter, Soro declined, stating: “I cannot comment on a matter that is before the court.”

But President Ouattara did comment at length on the matter. Asked pointedly about Koné’s arrest by a reporter during the same newsconference in Niamey on 24 October, the president answered, pretty much annoyed: “You are talking about an arrest. No one has been arrested. Someone is being detained while awaiting trial because the investigators have found six tons of weapons at [his] residence. That is not normal. Côte d’Ivoire is a lawful country, and the law is the same for everyone without exception.”

Soro’s so-called ‘patriotic forces’, the military component of the rebellion he led in 2002 against Gbagbo, were instrumental in leading his coalition with Ouattara to victory against the same Gbagbo in April 2011, sadly after a quasi-civil war that claimed more than one thousand lives, according to U.N. sources. It’s not clear how much military influence Soro still has, but a lingering quarrel between the one-time allies, many analysts interviewed for this article fear, is not good for Côte d’Ivoire or the West African region as a whole.

The “sacred union” of sorts between Ouattara and Soro in late November 2010 following former President Gbagbo’s stubborn refusal to leave office after losing the election that year to Ouattara helped restore the rule of law in Côte d’Ivoire, a regional economic engine that carries whopping 40% of GDP in the 8-nation West African Economic and Monetary Union. Ouattara, a fine product of the West African Central Bank and Bretton Woods institutions, has performed a miracle in turning Côte d’Ivoire’s economic engine back on, with double-digit GDP growth rate year after year. Abidjan, the largest city, looks now like a vast construction site with hotels, business offices and residences popping up all over. An analyst in the highest political circles in Abidjan tells The African both men, whom he describes as patriotic, are aware peace and dialogue are essential to keep the momentum going.

It appears the much-prepared—and later highly-publicized—3 November meeting of these two political giants, with Ouattara wrapping his arm around Soro for the press and the entire world to see, is saving the relationship. Soro, who boycotted the convention of the ruling party held in September, despite Obasanjo allegedly insisting that he attend, is now one of the 33 vice presidents of the highest echelon of the party. The announcement was made on 21 November by the party’s new president, Henriette Dagri Diabaté, undoubtedly not without the consent of President Ouattara. Significantly, the speaker of the parliament’s name appears at the top of the list.