The African factor in Bill Clinton’s impact on Hillary’s run for the presidency

BY PETER SESAY

In the very first presidential debate and several times thereafter, former secretary of state Hillary Clinton, the first serious woman candidate for the presidency of the United States, stated that she was not running for her husband’s third term or President Obama’s—though she added she might seek her husband’s advice about economic matters. She also later made it clear she would build on Obama’s legacy. However, former president Bill Clinton’s legacy soon became front and center in the former secretary of state’s courtship of the African American electorate, a large core of the Democratic party—since the adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1965—whose vote has helped many Democratic presidents, including Bill Clinton, win the election.

After narrowly beating her opponent, Vermont senator Bernie Sanders, by a razor-thin 1% point in the Iowa caucuses, only to be crushed by the 74-year-old populist democratic socialist in the New Hampshire caucuses the following week, Hillary Clinton badly needed to win the following caucuses in Nevada or see her momentum evaporate, with her campaign taking a serious mental blow. She soundly beat Sanders in Nevada with 5% points thanks to the African American and the Latino votes. The ensuing big psychological boost grew larger with her crushing victory in the hard-fought South Carolina caucuses which she won on February 27 with 74% points, garnering 84% of the African American votes. She achieved that despite her opponent receiving the endorsement of a number of African American heavyweights, including social activist and former entertainer Harry Belafonte, and film director Spike Lee. Clinton’s runaway victory during the Super Tuesday votes when 11 states, primarily in the south, held primaries and caucuses, would not have happened without the black vote. But not every African American thinks Clinton deserves the black vote.

Read more: Why Hillary Clinton is the best candidate for president

The haunting 1994 crime bill

The Clintons have had an indisputable love affair with black America for decades. However, many voters, including African Americans (some of whom actually have confronted Clinton on the campaign trail), have been quick to point an accusatory finger at former president Bill Clinton’s record in office, especially his 1994 crime bill that, while reaffirming the president’s commitment to fighting crime—as part of an overall strategy aimed at winning back white southern voters the Democratic party had lost to the allegedly tougher-on-crime Republican party—put African Americans behind bars by the thousands, destroyed black lives and families, even robbing some of them of the opportunity to start a new life once out of prison. The longstanding disproportionate number of imprisoned African Americans and the unfair treatment of blacks by law enforcement and the justice system are irrefutable facts. Also indisputable is the fact that President Clinton has contributed to mass incarceration more than any other president since 1980.

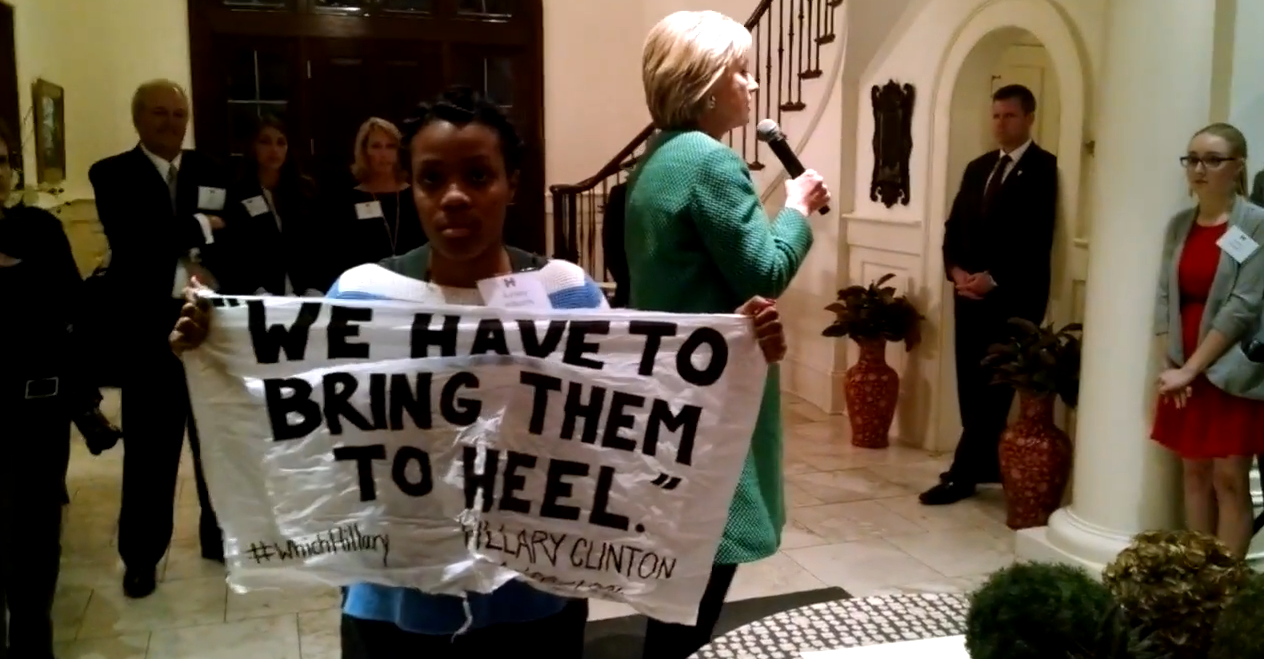

Hillary Clinton’s lobbying for the legislation and her overall involvement with her husband’s administration link her to the crime bill, and many feel she shares a responsibility in the matter. Moreover, critics recall the offensive, racially-coded remarks the then-first lady made with regard to black children: “They are not just gangs of kids anymore,” Clinton said, adding: “They are often the kinds of kids that are called ‘super-predators.’ No conscience, no empathy. We can talk about why they ended up that way, but first we have to bring them to heel.”

Political savvy

Confronted on the campaign trail by African Americans about the 1994 crime bill, Hillary and Bill Clinton now express regret about the bill. The former first lady also refers to her support for criminal justice reforms to reverse some of the damages of that law, not to mention her policy plans aimed at helping minorities in many ways.

The Clintons are known to be smart, sometimes cunning, political animals. Hillary Clinton wasted no time in labeling “a crime” the lead-contaminated water issue in Flint, Michigan, a city with a 57% African-American population where the authorities knowingly let the population drink lead-contaminated water to save money—which has caused several health issues. She visited the city (as did her opponent Bernie Sanders), and blasted the Republican governor of the state in a high-profile speech. Clinton also finally embraced the “Black lives matter” movement (an activist movement that campaigns against violence toward blacks) and was seen on the campaign trail surrounded by the mothers of four victims of police brutality. In her victory speech on March 1st following the Super Tuesday primaries and caucuses, she said: “We need to make America whole again,” in reference to her commitment to tackle the issues facing minority groups.

Clinton’s very high scores topping 80% or more among African American voters despite the charm of her charismatic (if utopian) democratic socialist opponent Bernie Sanders indicates that the criticism stemming from the 1994 crime bill (among others) has so far not been sticking. Several African American political icons, including John Lewis, a congressman from Georgia who marched for civil rights alongside Dr. King and the only living “Big Six” leader of the African American Civil rights movement, and Jim Clyburn, the influential congressman from South Carolina, squarely threw their support behind her. And, indeed, there is more to Bill Clinton’s legacy than the 1994 crime bill that can serve as an incentive for African American voters to cast their ballots for his wife. The 42nd president’s legacy to Africa, which contrasts with that of his most celebrated predecessor of the 1980s, Ronald Reagan, is a good example.

The benefits of Bill’s Africa policy

The Reagan administration’s policy toward Africa was arguably the darkest hours of U.S. relations with Africa over the past few decades, with the Republican president using his so-called constructive engagement policy to block United Nations’ and congressional efforts to impose economic sanctions on the apartheid regime in South Africa as a way to pressure the racist government to end the oppressive apartheid system. Instead, the administration sought to use incentives as a means of encouraging South Africa to gradually move away from apartheid. But the anti-apartheid movement grew so strong inside and outside the U.S. that the president’s veto of the 1986 Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act was easily overturned by the required two-thirds majority vote in Congress, thus paving the way for U.S. divestment from South Africa which ultimately brought down the apartheid system. That policy, in the name of which Reagan heavily armed the late Angolan rebel leader Jonas Savimbi, thereby prolonging one of the longest bloodiest civil wars in Africa, also put Washington at odds with the entire Sub-Saharan region via the Organization of African Unity. On the opposite side of Reagan’s poisonous constructive engagement policy, President Clinton’s Africa policy built deep-rooted ties with Sub-Saharan Africa in a way no U.S. president had ever done before him.

In an article titled “President Clinton’s Legacy to Africa” published in the March 2001 issue of The African, reporter Usman Mama quoted Edward J. Caselle, Assistant Deputy Secretary of State for Market Access and Compliance in Clinton’s Department of Commerce, as saying:

“There is no other group of countries in the world where the American government apparatus has been focused to try to figure out ways to be helpful to improve lives and the economies more than it has in Africa. I sit around the table with people from the Department of Energy, the Departments of Agriculture, Labor, our Small Business Administration, and we think what programs do we have in our own departments that we can bring to bear to make a difference in Africa.”

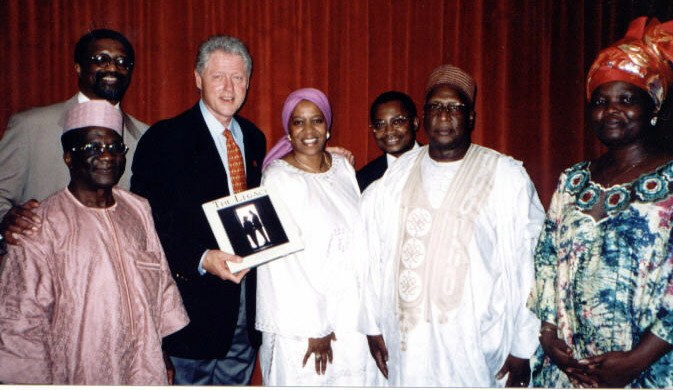

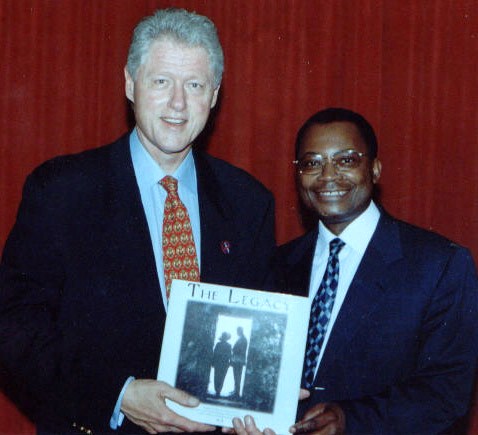

During Clinton’s second term, almost all of his cabinet members took at least one trip to Africa. Very early on, his Commerce Secretary, Ron Brown, traveled across the region in an effort to promote trade between African countries and the United States and to fight for a level-field conducive to American companies competing fairly with others. The attendance of his Transportation Secretary, Rodney Slater, at the Fourth African-African American Summit in Harare, Zimbabwe in 1997 is just one example of several of his cabinet members acting as his envoys at various major events in Africa. This is not to mention the president’s several trips to Africa, two as president and several more since leaving office.

Read more: President Bill Clinton’s legacy to Africa

U.S presidents’ state visits to the young countries in Africa, the majority of which became independent in 1960, are new. President Clinton was only the second U.S. president to make a state visit to Africa after President Jimmy Carter’s trips to Nigeria and Liberia in 1978, and the first one to visit the continent twice during his tenure. The president went to as many as eight countries in several regions of the continent, not to mention his several visits after leaving office for his humanitarian works. The 42nd president has become such a regular in Africa and so much loved that in his speech to welcome President George W. Bush on July 12, 2003 in Abuja, the capital of Nigeria, then-Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo said: “President Bush being with us at this time is the sort of accident we should be praying to God to always have.”

Read more: President Bush’s legacy to Africa

Blacks hail Clinton’s legacy to Africa

Not all African Americans embrace their African ancestry. Many among those who do and who follow U.S. foreign policy matters have hailed President Clinton’s unprecedented robust policy to Africa. Dr. Erieka Bennett, an African American who is the African Union-endorsed ambassador for the African diaspora, is also the vice president of The African Communications Agency, an organization whose publishing unit has captured former president Bill Clinton’s legacy to Africa in a book titled The Legacy, an upscale book that gives detailed and profusely-illustrated account of the president’s Africa policy through the statements of key African and African American political, business and community leaders. To expose the former president’s legacy to a wider audience, African oil mogul Samuel Dossou-Aworet financed the production of the French version of the book.

When then-Republican presidential candidate George W. Bush stated during the second presidential debate of the 2000 election that “Africa is not part of U.S. strategic interests,” the statement triggered an uproar among the African American elite who challenged the president about the unwelcome remarks. (Africa may not be part of U.S. strategic interests like the Middle East or other world’s hot spots, but President Bush’s African record proved to be impressive.) The African American reaction to Bush’s comments indicates that while Africa may not directly influence the outcome of the U.S. presidential election, the historical bonds between African Americans and the continent some of them call “the motherland” may carry a little weight in their support for Hillary Clinton, the Democratic presidential candidate whose brilliant (if flawed) husband African American novelist Toni Morrison has named “the first black president.”