Amr Muneer Dahab: The impressive journey of an engineer who juggles professional career and creative writing

BY USMAN MAMA

Regardless of the artistic form, artistic talents are usually born in the artist at an early age. Amr Muneer Dahab, a Sudanese-born essayist, literary critic and poet, is no exception. This electrical engineer who juggles his professional career and writing, tells The African Magazine that his poetic talent emerged while he was in high school. He has since expanded his artistic field to shine as an essayist and literary critic, and has been graced with several awards in the process.

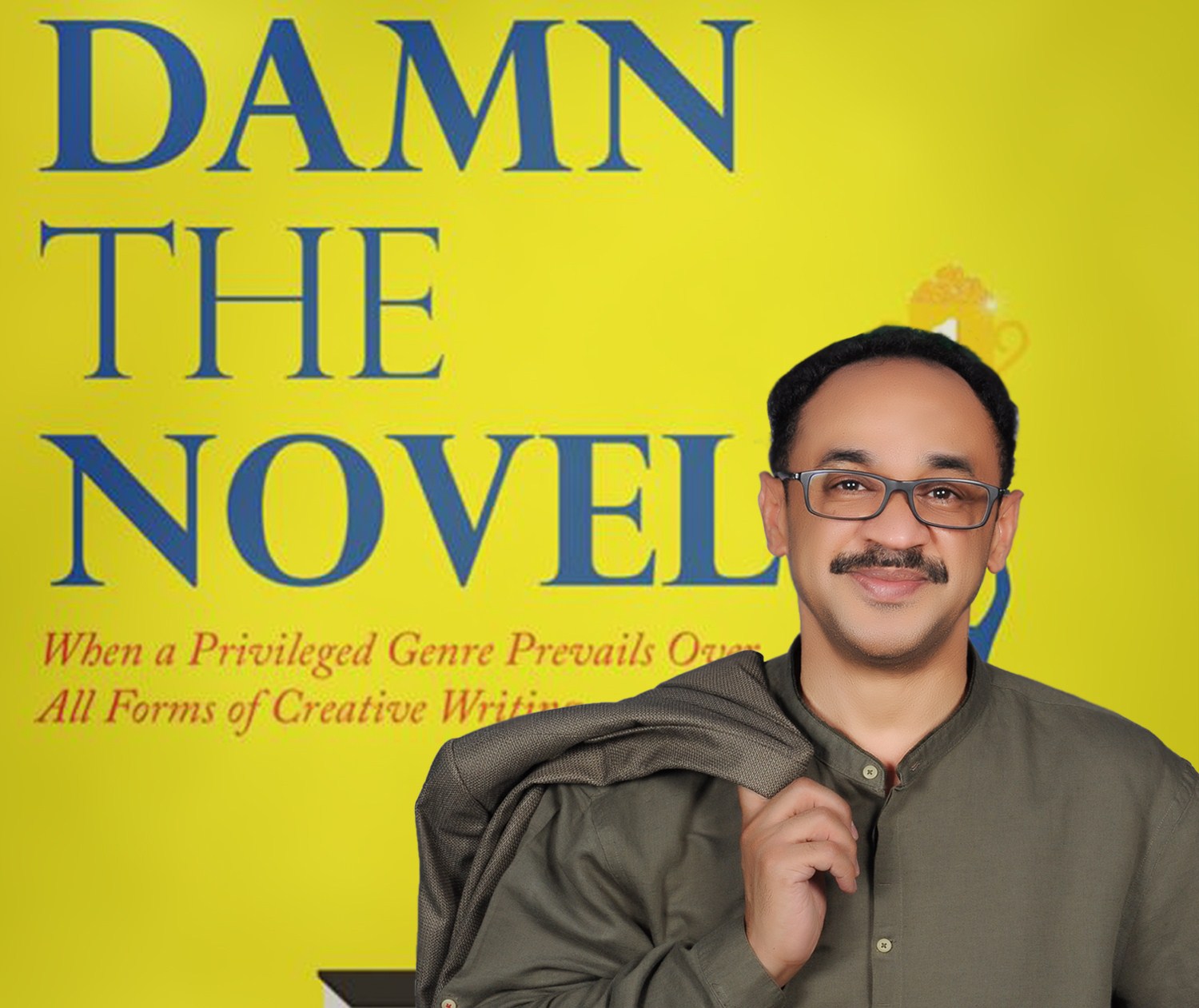

Before the publication of his recent book, “Damn the Novel: When a Privileged Genre Prevails Over All Forms of Creative Writing,” Dahab was credited with more than twenty books, all written in Arabic. The following are the titles and description of some of them in English.

No Compulsion in Revolution:

In this book, Dahab criticizes the state of holiness attributed to the revolution uprisings in the Arab world in late 2010, and even to any revolutionary act in any place and time in general. As evidenced in numerous parts of the book, the writer does not advocate depriving people of their right to speak up against tyrannical regimes. But he feels such right should be exercised freely and spontaneously, not as a process of actions dictated by this or that rebel group. Dahab asserts that his book is not in defense of corrupt authoritarian regimes, adding that it is more important to investigate the potential perspectives than to overthrow a corrupt regime, as anarchy may be the most lethal and corrupt alternative. Therefore, Dahab sees that the way to establish the desired democracy is to ensure “the eradication of the great dictator who lies within each of us, and be given the authority to take over our conduct in terms of the way we bring up our children, and over the methods we follow when given a position or a mission.”

O Writers Be Humble:

The book deals with a range of controversial issues about writing and writers alike: Why did writers fail to make writing a profession that can guarantee them dignified (or even luxurious) life? Expecting the following answer: The reason lies in people’s desertion of books. Dahab inquires about professions that have attracted the attention and interest of people. Thus, the book investigates the literary, social and cultural arena directly related to writing, asking questions and anticipating what is going on in the recipient’s mind without imposing an answer on the readers. “O Writers Be Humble” seems to be a sound critique whereby the author attempts to tackle many issues under titles such as “What Writers Have Never Had in Mind,” “Classic Arabic Victims,” “On the Gates of the Rich,” “Natural Selection of Writers,” “What Prevents a Writer from Resigning,” “The Writer’s Muscles,“ and others. Dahab says that he wanted the book to be a rebellious discovery in favor of writing and not against it. Accordingly, he dedicates the book to writing itself “confirming its virtues and pardoning its sins.”

Your Bedroom in Globalization:

This book deals with the impact of globalization as seen by an observer who interacts with its new waves, disregarding the estimates and promises of globalization research centers all around the world, basically in the West and in the United States specifically. “Be Aware of USA,” “How Globalization is Made,” “Bedroom in the Emirates and Living room in Canada,” “Globalization and Sex,” “Why Should We Speak Clean English?”, “Globalization’s Frustration,” and “Globalization and Writers of the Masses” are some of the titles through which Dahab focuses on the influence of globalization on people (at home, on the streets, in the work places), on how they spend their weekends in shopping malls, and on other aspects of personal and social life, especially in the Arab world. The writer approaches the subject matter beyond the traditional studies about the impact of globalization on politics, economy and similar arenas.

Arab Genes:

This book, as stated in its introduction, is not about the Arab character as a whole, but rather “that part of the character of Arabs dealt with behind the closed doors of secrecy/privacy. More precisely, the book is a deliberate reading of Arab national character and its national variants in accordance with its context.” It consists of many parts under titles such as “The Levantine and the Moroccan,” “What We Should Learn from Algeria and Egypt,” “The Hierarchy of Arab Creators,” “The Character of Iraqi People,” “How Others boast About Arabism,” “The Maghreb’s Got Talents,” “What Do We Lack to Become Masters,” In the introduction to the book, the author hopes readers could enjoy reading the book “being able to get rid of the authority of prejudices and, more importantly, of any national chauvinism with regard to this country or that throughout the wider Arab world.”

O Old Man:

The following story told by the writer sums up the theme of the whole book: “I was sitting with a teenager a few generations younger than me. I tried to melt the ice of coldness that seemed to take over our conversation while we were watching TV: ‘What do you think of these new actors?’ He replied: ‘Where are these new actors?’ I was smart enough to realize that the ‘new actors’ were in fact the same generation of the young man. However, I did not get the lesson, since I told the young man in question about a scene from a famous comedy play, and waited for him to laugh. He did not, and looked surprised in response to my emotional overload. I asked him: ‘Don’t you remember the scene?’ He even did not hear about the play and did not know any of the characters whose fame has survived for long years. That was to be expected, given the gaps existing between generations, but I was (maybe without being aware of the fact) trying to live a different time that is not mine. Furthermore, I was trying to make a younger man live my time. Both acts seemed to be two sides of one coin: ignoring the impact of time either by engaging oneself in the midst of young people, or by dragging them to live a time they have no connections with.”

Other book titles:

Feelings and Ideas I Do Not Own (2018); Memories of Easygoing Students (2016); On the Margins of the Sudanese Character (2015); Some of My Improprieties (2015); Tales of a Poor Expatriate (2014); Wisdom Highway (2011); The Sudanese Character in the Eyes of the Sudanese Elite (2010), and Sudanese Genes (2010).